Horses have an interesting digestive tract; they have a large hindgut where fermentation takes place. They rely heavily on this process for optimal digestion as well as energy production. Compared to other animals, horses have a lower enzyme activity at the beginning of their digestive tract. This simple difference indicates that horses are not meant to get a significant portion of their energy from sugars.

The primary energy source for horses are volatile fatty acids (VFAs). VFAs are produced because of the fermentation that takes place in the hindgut. It is estimated, that about 70% of the horse’s energy requirement should be from VFAs.

If you are familiar with the various types of carbohydrates, you will have likely heard the terms non-structural carbohydrates and structural carbohydrates. Structural carbohydrates are not digested in the foregut but digested by the microbial population in the hindgut of the horse. This process is what produces VFAs. The feeds that are rich in structural carbohydrates include hay, pasture, processed forages such as hay cubes, as well as other fiber sources such as beet pulp and grain hulls.

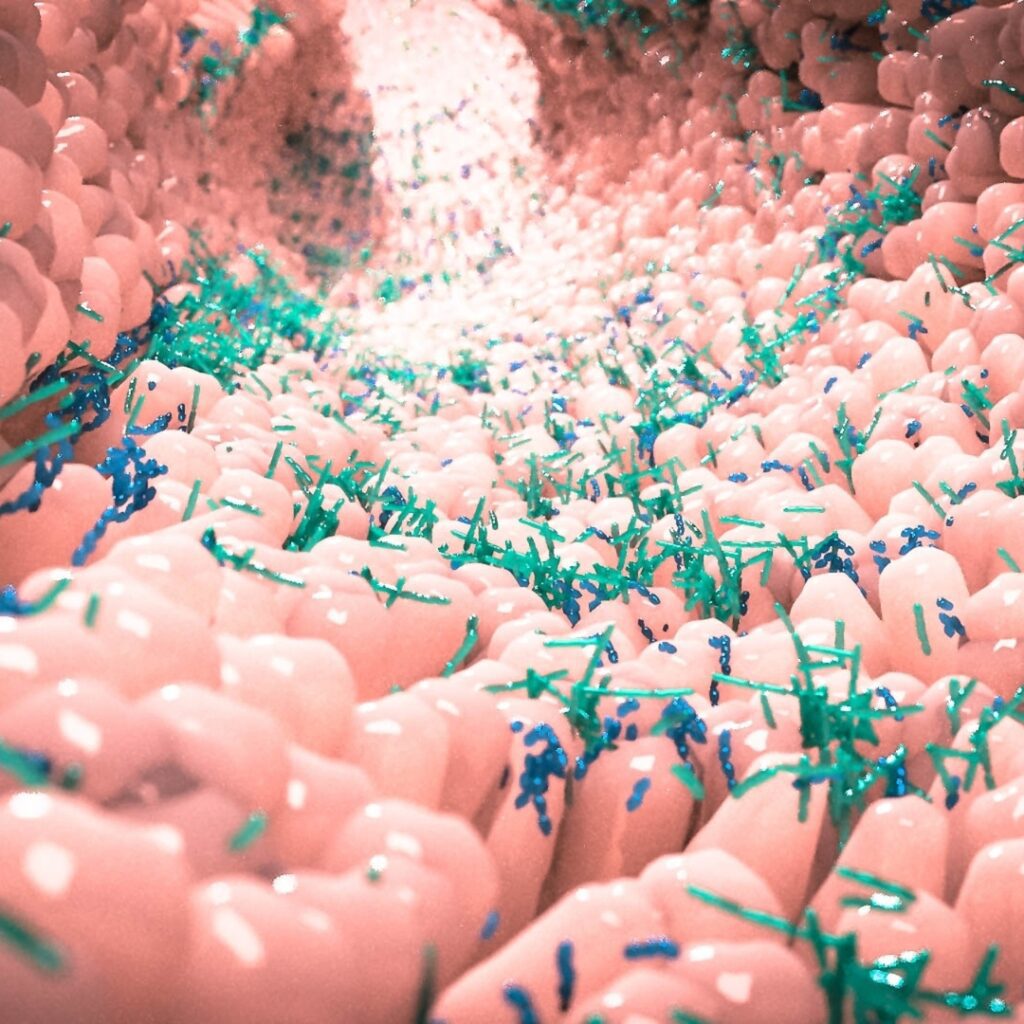

When the VFAs are produced by the microbes, they are absorbed through the hindgut epithelium in the cecum and colon. From there they are distributed throughout the body to be used as energy. For horses, the three most common VFAs are acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Acetate is the only one of the three VFAs that can be directly absorbed in the bloodstream and used for energy, propionate and butyrate must first be converted to other compounds prior to use for energy.

As mentioned above, the hindgut optimally works by breaking down structural carbohydrates. When we feed ingredients such as high-starch meals, lactate is produced which drops the pH of the hindgut making the environment more acidic. When the hindgut pH drops, the term we use is hindgut acidosis. When this occurs some of the beneficial microbes die off. Thus, disrupting the entire hindgut ecosystem.

A study published in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science in 2021 evaluated the impact on the hindgut when a portion of a performance horse’s grain intake was replaced with soluble fiber. In this study, each horse received each diet in a 3 x 3 latin-square design with a washout period of 21 days between diet treatments. The three diet treatments were:

1) High-fiber diet – 100% hay

2) High starch diet – 55% hay, 45% barley

3) High soluble fiber diet – 50% hay, 21% barley and 29% beet pulp

During the washout periods the horses received ad libitum hay. Their results showed that the high-fiber and high-soluble fiber diets results in increased concentrations of VFAs. The authors concluded that replacing part of the cereal grain intake for performance horses with soluble fiber such as beet pulp can help to limit the dysbiosis in the hindgut while still maintaining a high energy supply through the fermentation of the soluble fiber.

One last area of research that I would like to touch on regarding this subject is the variability in the microbial population between horses. This study was published in 2023 and compared the microbial population of different horse populations. What I found most interesting is they could evaluate both feral and domesticated horses. The populations of horses they evaluated were: feral horses living on the Outer Banks of North Carolina who eat native grasses and island grasses; horses from the NCSU Equine Educational Unit that are predominantly kept on cool season mixed pastures and may be supplemented with hay and concentrates from time to time; and finally, privately owned horses that are fed mixed diets consisting of hay, pasture and concentrates.

The authors illustrated that there is a distinctive separation in microbial diversity between the populations, especially between the feral horses and the domesticated populations. They proposed the reasoning behind this to be due to the habitual diet differences influencing the composition of their microbiome within the hindgut. Super neat if you ask me!! So not only do we know that what we feed the horse directly impacts that hindgut ecosystem, but the populations of microbes will adapt to differing feedstuffs.

As a nutritionist, I consider this delicate ecosystem in the hindgut frequently, as it is crucial to equine well-being that it stays healthy! Therefore, making all feed changes slowly so that the microbial population has time to adapt is crucial. Additionally, ensuring that when starch is fed in the diet it is being fed in small meals to reduce the amount of non-structural carbohydrates that reach the hindgut and contribute to the potential drop in pH.

By: Madeline Boast, MSc. Equine Nutrition

References:

Gluck, C., Bowman, M., Layton, J., Stuska, S., Maltecca, C., & Pratt-Phillips, S. (2023). 3 A comparison of the equine fecal microbiome within different horse populations. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 124, 104305.

Grimm, P., Julliand, V., & Julliand, S. (2021). 67 Partial substitution of cereals with sugar beet pulp and hindgut health in horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 100, 103530.