Understanding why we do certain things in equine nutrition is important, and primarily ties back to the digestive anatomy. A horse’s digestive tract is unique and dictates what we feed our horses. Therefore, through understanding the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) it can provide you with fundamental knowledge to make informed decisions about equine feeding practices.

Horses truly evolved to be trickle feeders. They are prey animals that are meant to have frequent grazing to support their wandering lifestyle. Now of course, the lifestyle of domesticated horses is quite different from their wild ancestors – however, feeding in a way that is supportive of their anatomy is crucial to ensure optimal health.

Horses are non-ruminant herbivores that rely on hindgut fermentation to support their fibre-based diets. A few of the distinguishing features of the horse’s GIT is the relatively small stomach and the large hindgut. To keep it simple, the digestive tract is going to be divided into two main parts: the foregut and the hindgut. We start this walk through of the GIT at the beginning, the mouth!

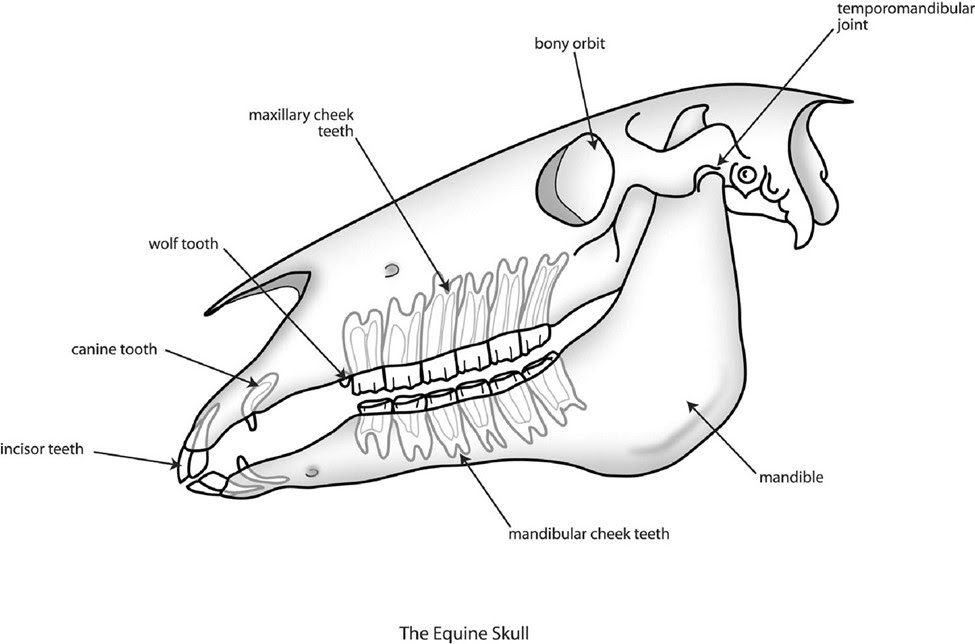

The mouth of the horse is where digestion begins. Of course, the horse must first grasp the feed. The prehension of feed is done by the lips and teeth. The horse will then chew the feed. They chew in a circular motion that grinds the feed to reduce the particle size.

Adult horses have hypsodont teeth which means that they are suited to a more abrasive diet as the enamel is worn down over time. Other animals that have hypsodont teeth are cows and deer. A horse’s teeth continually erupt throughout the animal’s lifetime. With the more abrasive diet of herbivores that horses have, their teeth wear away through the grinding motion that they use to chew. With a forage-based diet it is estimated that 2-3 mm per year are worn away.

Below is an image showing the basic tooth anatomy:

Image retrieved from: https://www.texasequinedentist.com/blog/2013/06/equine-skull-anatomy-interesting-facts/

When wear is not even this is when the issues such as hooks occur. Hence the reason why it is crucial that your veterinarian performs regular dental exams on your horse and floats their teeth when required. Floating involves removing the sharp enamel points that often develop when the teeth are not worn down evenly.

Routine dental exams are crucial as when the teeth are worn unevenly, the chewing motion can be restricted. The negative impact on the horse when there is a restriction in chewing motion is immense and often includes a loss of body condition and dental pain.

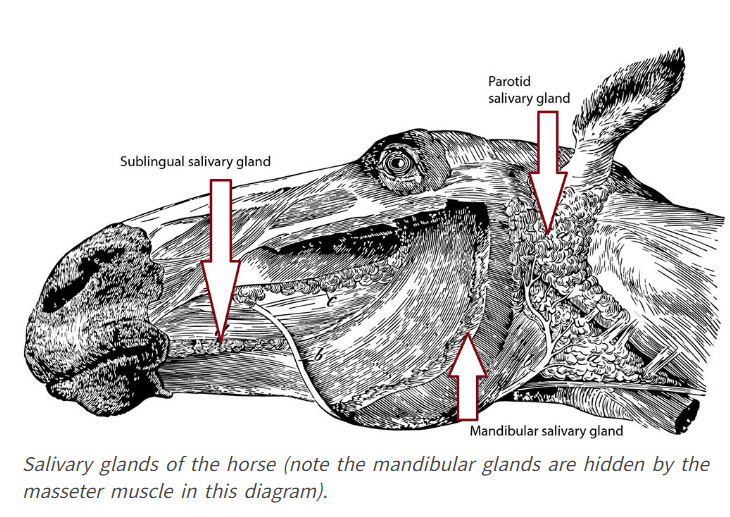

Shifting our focus away from chewing, the other critical event that takes place in the mouth is salivation. In the horse, there are three pairs of salivary glands. They are the mandibular, the parotid and the sublingual. Between these three pairs of glands about 35-40 litres of saliva can be produced each day. The amount of saliva that a horse produces will depend on the feed they are consuming, for example, the chew time for hay is longer than for grains, therefore more saliva will be produced when the horse is consuming hay.

Below is an image showing the location of the various salivary glands:

Image retrieved from: https://eqlifemag.com.au/issues/88/from-the-horses-mouth-salivary-glands/

Unlike many other mammals, such as humans, horses do not salivate in anticipation of food. The chewing motion activates saliva production. Therefore, when there is less chewing, there is less saliva produced. Consider the chew time difference between hay and concentrates. It is estimated that for 1-pound of grain, the chew time is about 5 minutes. However, if we switch it to 1-pound of hay the chew time increases to 20 minutes! A significant difference that is going to influence their saliva production as well.

Most people know that saliva is important to moisten the feed, however it is also critical for buffering the acidic environment of the GIT. Equine saliva is primarily water; however, it does contain calcium and chloride as well. It has been well documented that saliva has a positive impact on the pH of the stomach (making it less acidic). Gastric ulcers are a prevalent condition in horses, therefore having adequate chew time to produce saliva can make a significant impact on preventing the stomach environment from becoming too acidic.

A 2010 study (O’Neill et al.) investigated dental differences in 60 Thoroughbred-type horses. Half of the horses were kept on pasture year-round, and the other half were stabled 24 h/day. The stabled horses were fed a high-energy cereal based diet. It was concluded that the stabled horses had a significantly higher occurrence of dental abnormalities than the horses housed on pasture. However, it should be noted that horses in both groups did develop sharp edges of the cheek teeth. Therefore, their results agreed that a fibre-based diet that is grazed results in fewer dental abnormalities, however routine dental care is still required even on what is considered a ‘natural diet’.

To conclude, there is a considerable amount of interesting information to share about the equine gastrointestinal tract. Oftentimes, the mouth may be overlooked, however it plays a crucial role in digestion and nutritional well-being. When evaluating your horse’s diet, consider the chew time that their feed supports as that not only impacts their dentition but also has a significant impact on their salivation and stomach acid buffering abilities. If you have any questions about your horse’s nutrition, don’t hesitate to reach out at balancedbaynutrition@gmail.com

By: Madeline Boast, MSc. Equine Nutrition

References:

Houpt, K. A. (2006). Mastication and feeding in horses. Feeding in domestic vertebrates: from structure to behaviour, 195-209.

Alexander, F. (1966). A study of parotid salivation in the horse. The Journal of Physiology, 184(3), 646.

Dixon, P. M. (2002, December). The gross, histological, and ultrastructural anatomy of equine teeth and their relationship to disease. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (Vol. 48, pp. 421-437).

O’Neill, H. M., Keen, J., & Dumbell, L. (2010). A comparison of the occurrence of common dental abnormalities in stabled and free-grazing horses. animal, 4(10), 1697-1701.

Carmalt, J. L., Cymbaluk, N. F., & Townsend, H. G. (2005). Effect of premolar and molar occlusal angle on feed digestibility, water balance, and fecal particle size in horses. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 227(1), 110-113.

Janis, C. (1976). Janis, C. (1976). The evolutionary strategy of the Equidae and the origins of rumen and cecal digestion. Evolution, 757-774.

Copyright © 2024 Balanced Bay Nutrition | Site Crafted by Bay Mare Design